Amber Guinness Shares Her Tuscan Kitchen Secrets

Amber Guinness shares her love for Tuscan winter cuisine, blending traditional recipes, hidden gems, and the philosophy of “quanto basta” to inspire intuitive, unhurried cooking and cultural exploration.

Amber Guinness is a name synonymous with the rich tapestry of Tuscan cuisine and culture, a true ambassador of its winter comforts and culinary secrets. Born in London but rooted in the rolling hills of Tuscany, Amber’s life at Arniano, the restored farmhouse near Siena, has shaped her into a storyteller of food, place, and tradition. Her work is a celebration of the Italian way of life, where instinct and simplicity reign supreme, and the philosophy of “quanto basta” — as much as you need — becomes a guiding principle for both cooking and living.

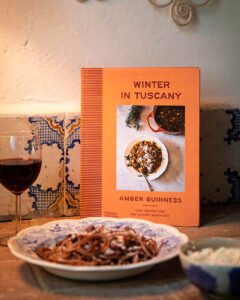

Her latest cookbook, Winter in Tuscany, is more than a collection of recipes; it is an invitation to slow down, to savour, and to immerse oneself in the rhythms of the season. Amber’s writing evokes the warmth of a Tuscan kitchen, the aroma of simmering broths, and the artistry of dishes that elevate humble ingredients to something extraordinary. From the robust flavours of spaghetti all’ubriacona to the delicate comfort of mini malfatti in broth, her recipes are imbued with a sense of place and purpose, offering readers a taste of Tuscany’s soul.

What sets Amber apart is her ability to intertwine her artistic sensibility with her culinary expertise. Her background as a painter infuses every page of her book with a visual richness, a reminder that food is not just sustenance but a form of beauty and expression. She guides us to hidden gems like Monte Oliveto Maggiore, where the monks’ saffron speltotto embodies centuries of tradition, and to cosy trattorias where long, indulgent lunches are a way of life. Her approach to cooking is unhurried, reflective, and deeply connected to the land and its bounty.

Amber’s work also challenges misconceptions about Tuscan cuisine, showcasing its vegetarian diversity and the central role of vegetables like cavolo nero. She brings authenticity to her recipes, often gleaned from cherished family traditions or the kitchens of beloved local restaurants. Her dedication to perfecting each dish, whether by watching nonna Anna stir her zuppa di farro or recreating the pillowy lightness of polpette al Limone, speaks to her passion for sharing Tuscany’s culinary heritage.

In this interview, Amber Guinness invites us into her world — a world where cooking is an act of love, where food is a celebration of life, and where winter in Tuscany is a season of warmth, togetherness, and endless inspiration. Her words and recipes are a gift, reminding us to embrace the philosophy of “quanto basta” not just in the kitchen, but in all aspects of our lives. Amber Guinness is, without doubt, a beacon of Tuscan culinary artistry, and Winter in Tuscany is a testament to her enduring love affair with this enchanting region.

The “quanto basta” philosophy is central to your cookbook. Can you explain how this approach differs from traditional recipes and what benefits it offers home cooks?

The ‘Q.B.’ (quanto basta) approach represent so much of what I love about Italian cooking, these two letters illustrate in black and white that cooking a meal doesn’t need to be an exacting affair if you use your instincts. It literally means ‘as much as you need’ and if you leaf through any cookbook originally written in Italian you’ll see that in the list of ingredients for any recipes, many of them are followed by those initials. Basically, meaning you should add as much salt, flour, butter or oil, or whatever it might be, as is needed. It’s an approach that encourages you to use your instincts rather than painstakingly measure out olive oil when a glug or two will do. Instead, if you add ingredients little by little and most importantly, taste as you go, then the quantities (within reason) don’t matter too much and any ‘mistakes’ will usually be rectifiable. I love the sentiment behind it, that of not stressing too much or taking cooking too seriously, but instead of using your taste, touch, instinct and a little bit of common sense to make something tasty, which to me is a really wonderful philosophy for any home cook to remember.

Your book features many traditional Tuscan winter dishes. Which recipe are you most proud of, and why? What makes it particularly special or representative of Tuscan cuisine?

I really love the collection of recipes in this book. I love that there is something for every occasion and that many of the recipes elevate humble ingredients, scraps or cheaper cuts of meat to make something delicious for cold winter nights. One pasta dish that I’m particularly fond of is the spaghetti all’ubriacona (drunkard’s spaghetti) which is an old recipe from Chianti, designed to use up the scarti – leftover wine that wasn’t the best for drinking. I find it an unusual, interesting and very tasty recipe. The wine is cooked down in the pan with pancetta and onion until the alcohol has evaporated and spaghetti is cooked in a mixture of wine and water to impart some of the violet colour. The result is fabulous and has the added benefit of being a great recipe to use up that half drunk bottle of wine that’s been sitting on the kitchen counter for two weeks.

“Winter in Tuscany” is more than just a cookbook; it’s a journey through the region. What are some of your favorite hidden gems or lesser-known aspects of Tuscany that you share in the book?

Since I was a child living in Tuscany, my family’s favourite cultural outing has always been going to visit the abbey of Monte Oliveto Maggiore. It’s a beautiful working Benedictine monastery which sits in very lovely part of Tuscany called the Creti Senesi. The abbey is most famous for its cloister which is frescoed and depicts scenes from the life of St Benedict painted by Signorelli and Sodoma. The frescoes are spectacular and well worth a visit in the quieter winter months, when you may well have the place entirely to yourself. The monastery also has a beautiful church with a famous wooden inlaid choir stand. Their working farm makes one of the best olive oils in Italy (it was once voted one of the top 40) and they produce honey, spelt, saffron and wine. The monks kindly shared their recipe for saffron speltotto, which they developed as a way of using all the amazing produce they grow on their farm (homegrown spelt, saffron, white wine and olive oil). A visit to the monastery can be combined with a delicious lunch at the neighbouring restaurant, La Torre, a short walk from the abbey. La Torre is a fabulous family run restaurant serving typical Sienese dishes such as pici, tagliatelle and, when in season, white truffles. They also serve the wonderful wines made by the monks of Monte Oliveto.

You mention exploring Tuscany at a slower pace. How does this approach influence both the cooking and the overall experience described in the book?

I like doing everything more slowly in winter! It’s a time for being cosy, hibernating and hunkering down with a good book, or even better, over a good meal. It’s when I most relish being in the kitchen over a hot stove and not rushing, taking my time over the course of several hours to make broth, cook a peposo (black pepper stew) or make homemade pici with my son. When the nights draw in early, what better way to spend an afternoon? That’s true of taking in culture as well and exploring new places, there is no point overstretching your itinerary to take in all the blockbuster sites, why not choose one or two lesser known gems, perhaps one for the morning and one for the afternoon – punctuated by a long, indulgent lunch in a cosy trattoria – and really take your time to walk around and take in the beauty.

Many of the recipes highlight specific Tuscan ingredients (cavolo nero, stracchino, etc.). Can you tell us about one ingredient that is particularly special to you and why it plays such an important role in Tuscan winter cooking?

Possibly the most emblematic of all Tuscan vegetables is cavolo nero, or ‘black cabbage’, a type of brassica with no head, instead growing in long elegant dark leaves, similar to kale. The leaves feel almost rubbery and need cooking to become edible. Growing rampantly from the autumn into the new year in Tuscany, they are at their best when there has been a frost as the extreme cold tenderises the leaves. It’s one of my favourite vegetables and has long been used in Tuscany during the winter months to stir though soups, such as ribollita, stir fried with chilli and garlic as a side dish or be blanched and whizzed into a delicious wintery pesto to dress pasta. There is a lovely recipe in the book which is a cavolo nero pasta with walnuts and pecorino which is very warming on a winter’s night and makes one feel one is eating one’s greens whilst also indulging in some pasta!

The book includes suggestions for local wines. Can you recommend a specific wine pairing for one of your favorite recipes in the book, and explain why they complement each other?

As a rule of thumb, more robust full bodied wines go better with robust meatier dishes, while lighter, more acidic wines go with lighter dishes, or with melted cheese to cut through the fat. If I were to have a Bistecca Fiorentina (Florentine t bone steak), the best pairing I could suggest would be a good brunello di Montalcino, my favourites are from Tenuta Buon Tempo and Castiglione del Bosco. However if I was having the baked fennel with pasta and bechamel from the book (one of my favourite recipes), I would opt for something less full bodied so that the wine and creamy bechamel sauce didn’t over power each other, a good alternatice would be a Chianti Classico from Fonterutoli or a Rosso di Montalcino, also from Tenuta Buon Tempo or Castiglione del Bosco.

You run a painting school in your home outside Florence. How does your artistic background influence your approach to cooking and presenting the recipes in “Winter in Tuscany”?

Well, I suppose it means that I mind about aesthetics! Which translates into my loving a beautifully laid table or presented dish. I love a colourful meal and a sense of balance in flavours, textures and colours when planning a menu.

What is the biggest misconception people have about Tuscan cuisine, and how does your book aim to correct that?

Probably the biggest misconception is that it is entirely meat based and while it definitely has ‘meaty’ elements – Bistecca Fiorentina, wild boar stews and ragus, ect. Tuscan cuisine also celebrates vegetables and pulses in a myriad of ways. To this day, Tuscans are affectionally known in other parts of Italy as ‘I mangiafagioli’ (the bean eaters) and many of Tuscany’s famous soups and mainstay dishes are entirely vegan, being based around cannellini beans, chickpeas or spelt. Vegetables also play a central role, and cavolo nero, fennel, artichokes, radicchio, are all elevated to dizzying heights of deliciousness in winter. The fact that over half the recipes in this book are vegetarian highlights this. I’ve also included a chapter called ‘Piatti di mezzo’, meaning ‘in between dishes’ ie. Those which are vegetarian but don’t quite fit into the ‘Primi section of pasta and soup as they are too substantial, but also probably wouldn’t classify as a ‘secondo’ as they aren’t meat based or include pastry or an element of pasta.

What was the most challenging recipe to perfect for the book, and what lessons did you learn during the process?

There are two recipes in the book which are from two of my favourite restaurants in the world. One is the zuppa di farro – spelt and cannellini bean soup – which was always what I would order at Da Mario in Buonconvento if my dad took us there for lunch after school when I was a child and the other are the polpette al Limone – lemony meatballs -from Alla Vecchia Bettola in Florence. Both these restaurants very kindly shared their recipes with me, but the trouble was that there isn’t really a recipe for either, they are made in the restaurant kitchen the ‘quanto basta’ way, so they could only really describe the process rather than with any idea of quantities. In the end I had to go and actually watch both of these dishes being made as they weren’t turning out in my kitchen as they tasted in the restaurant. After that everything fell into place and the soup became the comforting, creamy thick base with plump little pieces of spelt floating in it I had always eaten as a child and the meatballs became as light and pillowy as at the Vecchia Bettola. The secret the soup as it turned out was to cook the spelt separately to the soup itself and add it just before serving so it retained its delicious texture with a little bite – step seemingly so obvious to nonna Anna, the proprietress, she didn’t think she needed to tell me when describing the cooking method to me. The secret to the meatballs was to use cheap, white sliced bread soaked in milk rather than breadcrumbs.

What’s your favorite thing to cook from the book for yourself or your family on a cold winter’s evening? What makes it so comforting?

Definitely Mama’s mini malfatti in broth. Malfatti are ricotta and spinach dumplings, sort of like gnocchi, which you poach and normally dress in sage butter or tomato sauce (there is a recipe for these versions in my first book) but my mother would always make mini malfatti to poach and serve in homemade chicken broth in winter. It’s so delicious, warming and comforting. There is something so lovely about when someone has taken the trouble to make homemade stock, to extract every last piece of goodness and flavour from a load of vegetables or meat. It’s hands off but takes patience, so I really appreciate it when someone serves it to me and conversely I make it to show people I love them and to bring them comfort as I find any brothy soup comforting and nostalgic. Broth is also a lovely vehicle for lots of good things, mini malfatti or little pieces of pasta, vegetables or poached chicken.

Editor’s Note:

Amber Guinness’s Winter in Tuscany is an evocative celebration of Tuscan winter living, featuring soulful recipes and rich cultural insights. More than a cookbook, it encourages slow living, creativity, and the joy of sharing food. Rooted in tradition and guided by quanto basta, this book beautifully embodies Tuscany’s culinary and cultural heritage.